It was a pleasure to read about the dramatic turnaround in the Bloomfield public schools. And it was extra special to recognize that one of our scholarship recipients has played a leadership role in this achievement.

Several years ago, the situation in the Bloomfield Schools was bleak. Test scores and graduation rates were low. Only half of the high school’s graduates enrolled in two- or four-year colleges.

The predominantly African-American school system offered a stark example of the achievement gap affecting minority and low-income students in Connecticut and throughout the nation.

Now, the picture is much brighter. According to an article by Robert A. Frahm in the CT Mirror, the dramatic improvement in academic performance in Bloomfield has captured the attention of state officials and education reform organizations.

Last year, 71 percent of 10th graders met the state proficiency standard on a statewide mathematics test, compared with 46 percent in 2011. And 89 percent of sophomores met the state standard in reading, up from 62 percent in 2011.

Bloomfield High School’s four-year graduation rate improved to 90 percent in 2014, from 74 percent in 2011. Last year, 72 percent of high school graduates went on to two- or four-year colleges, compared with 51 percent in 2009.

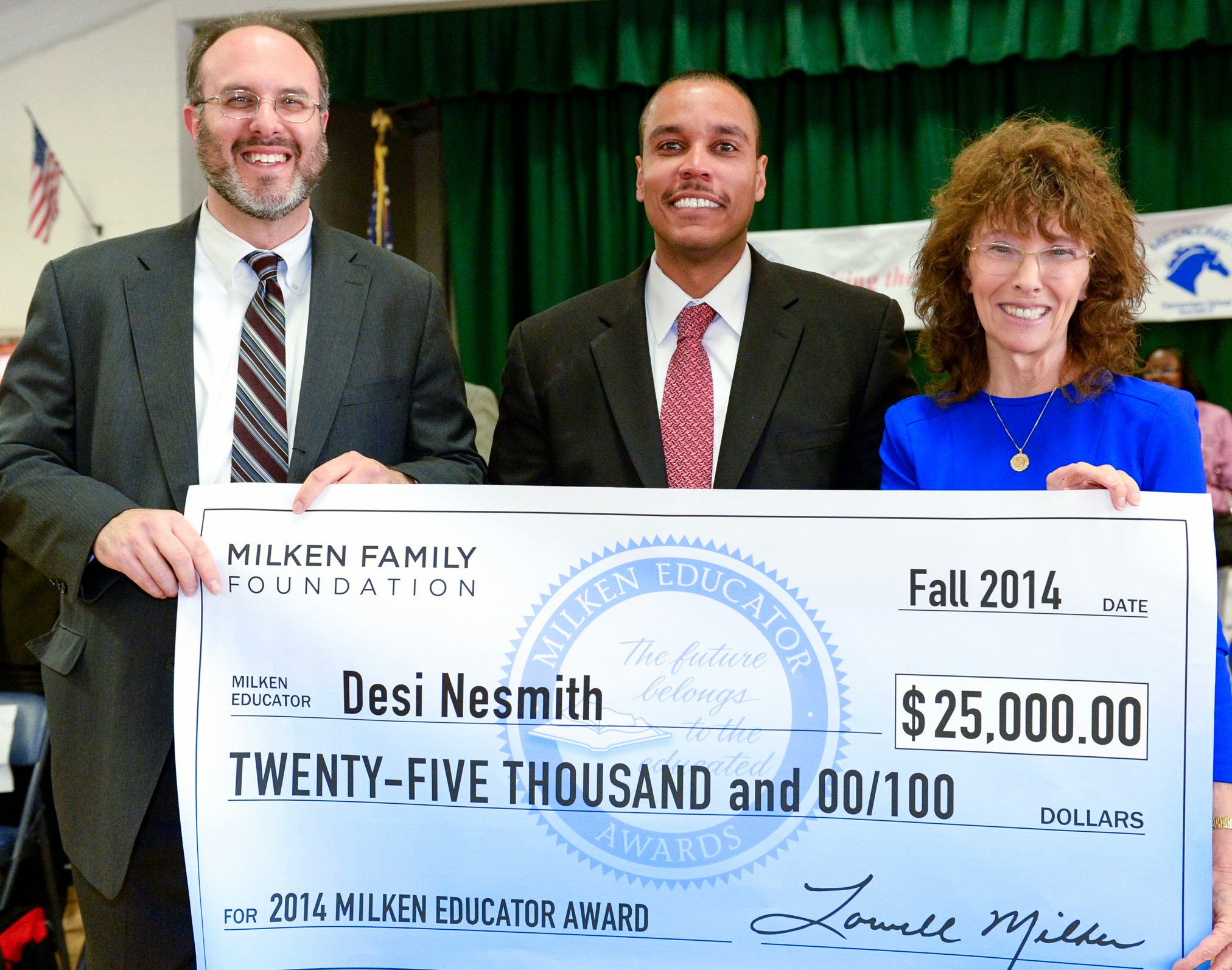

Dramatic improvements also have been accomplished in the lower grades, where 2000 Alma Exley Scholar Desi Nesmith has been a key leader.

In 2011, Mr. Nesmith was named principal of Metacomet School, one of two elementary schools in town. He was selected by James Thompson Jr., who had been named superintendent earlier that year.

Dr. Thompson had been hired to lead a turnaround in Bloomfield, based on his leadership record in the Hartford Schools. He had a vision of higher academic performance in Bloomfield, and Mr. Nesmith shared that vision.

Right at the start, the new principal established high expectations for academic performance at Metacomet. And his commitment to setting the bar high has paid off.

By 2013, third-grade classes had surpassed state averages in reading, writing and math on the Connecticut Mastery Test. The third-graders, almost all African-American and Latino children, far outperformed similar groups statewide. For example, 65 percent of Metacomet’s third graders met the state reading goal, compared with about one-third of minority third graders across the state.

What made the difference in Bloomfield? Dr. Thompson focused on strengthening academics, promoting good discipline and behavior, and forging ties with parents and the community. Teachers rewrote the curriculum to align it with statewide Common Core standards, and schools adopted new accountability plans.

The district started new after-school programs, added summer classes and provided additional training for teachers. Newly created school data teams regularly reviewed student academic performance.

The results caught the attention of the Connecticut Council for Education Reform (CCER), a statewide, business-sponsored non-profit group. The CCER issued a report describing the district’s reforms as a blueprint for narrowing the achievement gap.

Three years ago, Bloomfield received notoriety as one of 30 low-performing districts in the state designated for extra funding. Now, the CCER has singled out Bloomfield for making steady progress in all of its schools.

As someone who grew up in Bloomfield, attending Metacomet School in first grade, Desi Nesmith is gratified to have played a part in the resurgence of his hometown’s schools. But he and his colleagues are not resting on their laurels. They know there is much more to accomplish on behalf of the town and its students.

“We’re not complacent about it,” he said. “We’re not finished yet. There’s a long road ahead of us.”

Congratulations to Desi and all of his colleagues among the leadership and faculty of the Bloomfield Schools. Your achievement shows what can be accomplished through enlightened leadership that sets demanding goals and insists on accountability.

At the Alma Exley Scholarship Program, we have been focused on identifying committed future educators who have the potential to make a difference in the lives of their students. It’s most rewarding to see honorees like Desi Nesmith fulfilling their potential and having an impact.

– Woody Exley